Wickard v. Filburn

Congress may use its Commerce Power to regulate or prohibit activities

Facts Of The Case

Filburn was a small farmer in Ohio who harvested nearly 12 acres of wheat above his allotment under the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938. Filburn was penalized under the Act. He argued that the extra wheat that he had produced in violation of the law had been used for his own use and thus had no effect on interstate commerce, since it never had been on the market. In his view, this meant that he had not violated the law because the additional wheat was not subject to regulation under the Commerce Clause.

Question Did the Act violate the Commerce Clause?

A unanimous Court upheld the law. In an opinion authored by Justice Robert Houghwout Jackson, the Court found that the Commerce Clause gives Congress the power to regulate prices in the industry, and this law was rationally related to that legitimate goal. The Court reasoned that Congress could regulate activity within a single state under the Commerce Clause, even if each individual activity had a trivial effect on interstate commerce, as long as the intrastate activity viewed in the aggregate would have a substantial effect on interstate commerce. To this extent, the opinion went against prior decisions that had analyzed whether an activity was local, or whether its effects were direct or indirect.

Conclusion Sort: by seniority by ideology Unanimous decision for Wickard majority opinion by Robert H. Jackson Congress may use its Commerce Power to regulate or prohibit activities Congress may use its Commerce Power to regulate or prohibit activities provided the economic effects of such activities are substantial

Robert H. Jackson Jackson Harlan Fiske Stone Stone Owen J. Roberts Roberts Hugo L. Black Black Stanley Reed Reed Felix Frankfurter Frankfurter William O. Douglas Douglas Frank Murphy Murphy

Cite this page APABluebookChicagoMLA "Wickard v. Filburn." Oyez, www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/317us111. Accessed 7 Feb. 2025.

☆

When Roscoe Filburn dared to feed his family and cattle without government approval, and USDA fined him $117 for exceeding quota and harvesting 239 bushels of wheat, the Ohio farmer charged into one of the most consequential fights in U.S. history.

Reacting to a game-changing expansion in federal power, Filburn sued, contending his crop was beyond the control of Congress. The resulting legal battle turned Filburn’s land into the farm that birthed a monumental government grab via a mere 16 words of the Constitution—the Commerce Clause, which became the vehicle of federal reach into every facet of American life.

Eighty years later, Filburn’s court battle is the Lazarus case—resurrected daily. “He was way ahead of his time,” says Roscoe ‘Tom’ Filburn Jr. “My dad was just a small farmer, but he looked into the future and saw harm coming to our freedoms.”

Kicking The Hornet’s Nest

In 1940, the Second World War raged across the pond; Franklin Roosevelt was elected to a third term; Captain America was born in comic books; nylon stockings hit store shelves; Gone With The Wind debuted; and Roscoe Curtiss Filburn planted winter wheat.

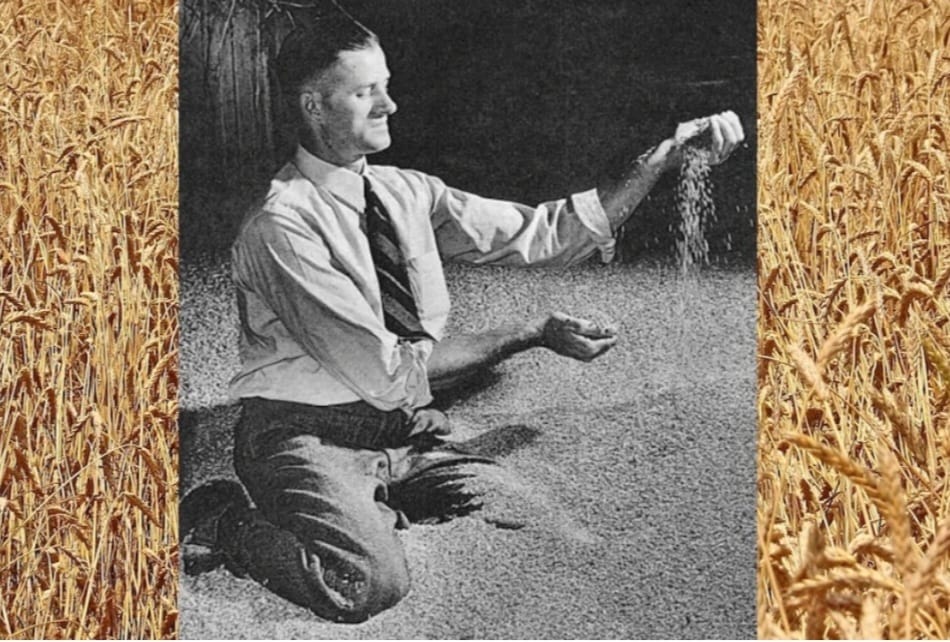

WHEAT READY TO CUT MS.jpeg

In late fall, Filburn, 38, planted 23 acres of wheat a stone’s throw northwest of Dayton on his Montgomery County farm in central Ohio. It was the age of transition from mule power to mechanization, and bushel-per-acre average U.S. yield was relatively lean: winter wheat, 14.1; corn 29.5; and soybeans, 20.7.

“Our family had been in the Dayton area since 1811 and farming was what my dad did,” says 82-year-old Filburn Jr. “Everyone called him, ‘Ross,’ and he was well-respected as a man to trust. He spoke up when he saw wrong and tried to make it right. We had a hammer mill to grind our own grain, and at the time we had dairy cattle.”

By government quota, via the Agriculture Adjustment Act of 1938, Filburn was permitted to grow 11.1 acres of wheat, yet he exceeded the allowance by 11.9 acres. Months after planting, in July 1941, Filburn harvested his 23 wheat acres and cut too much grain—462 bushels in total, of which 239 bushels exceeded his allotment. USDA levied a penalty of 49 cents per bushel for a fine total of $117.11, dropped a lien on his wheat crop, and seized his marketing card.

Filburn refused to pay the fine and declared that Washington, D.C., 500 miles east, had no power to regulate his yields in Ohio because he sold part of his wheat locally, fed a portion to his livestock, ground some into flour for personal use, and kept the remainder as seed for the next year.

“Basically, my dad said, ‘The government has no business in my wheat because it’s not going into the open market,’ Filburn Jr. explains. “He said, ‘I’m using it, not selling it. Therefore, leave me alone.’”

Filburn sued (1941) USDA and Secretary of Agriculture Claude Wickard (an Indiana farmer) in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio. Filburn won in a ruling issued in March 1942.

However, Filburn had kicked the hornet’s nest. At lightning speed—indicative of the federal concern over loss of power—the government fast-tracked the Filburn fight (Wickard vs. Filburn) to the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) roughly 60 days later.

The government was in panic mode.

Pontius Pilate

Roscoe’s rebellion hit a SCOTUS buzzsaw on May 4, 1942.

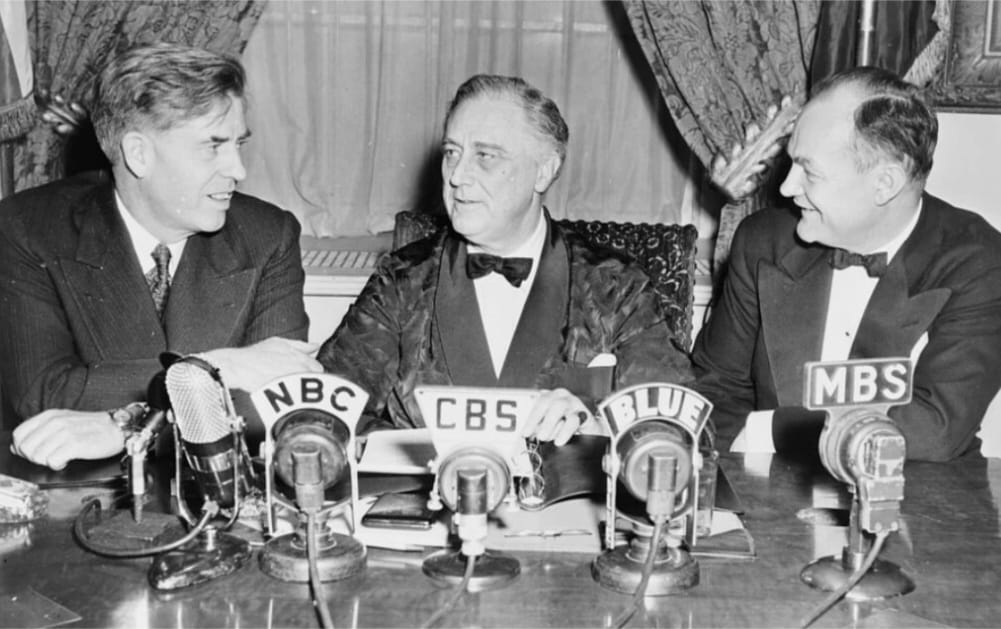

Wickard vs. Filburn was heard before nine justices—eight of them nominated by the sitting commander in chief, Roosevelt, and likely to back the president’s push toward an economy increasingly controlled by federal officials.

SCOTUS THE STONE COURT.jpg

SCOTUS made one of the most consequential decisions in U.S. history in November 1942, and ruled in favor of the government and against Filburn in an 8-0 (minus one justice due to a previous resignation) unanimous vote, redefining the Commerce Clause to declare Congress could regulate any activity, in or between states, that had an economic effect on commerce. Period. Full stop.

However, the Commerce Clause was a mere 16 words in Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution, giving Congress the power: to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.

Commerce, according to the founders, and particularly the Constitution’s driving author, James Madison, was trade. Only trade. Not manufacturing. Not energy policy. Not conservation. Not retail. Not agriculture.

Explicitly listed in the Constitution, Congress was given 18 powers, such as declaring war and coining money, but every other power kicked backed to the states, explicitly stated in 1789 by James Madison in the capstone to the Bill of Rights, the Tenth Amendment: The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.

A year prior, in 1788, Madison provided the same explanation in the Federalist Papers: The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the federal government are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the State governments are numerous and indefinite.

Yet, according to SCOTUS’ Wickard interpretation, the 16 words of the Commerce Clause were the most powerful tool of the regulatory state in U.S. history. There had been other Commerce Clause-related cases before SCOTUS, but the Wickard decision was the broadest, most expansive interpretation ever.

In a nutshell, SCOTUS gave the government an inroad to control anything and everything. Via the Commerce Clause, per SCOTUS, the government hand could reach any realm of American life via a connection to the economy—no matter how tenuous or thin the thread.

“In a Pilate-like sense, the Supreme Court washed their hands, and said, ‘This is Congress’ problem,’” explains Roger McEowen, Professor of Agricultural Law and Taxation at the Washburn University School of Law, and author of the Agricultural Law and Taxation Blog.

“They handed Congress the authority to regulate private economic activity that made no distinction between interstate and intrastate commerce. It was a dramatic, giant increase in regulatory power and set up precedent for government expansion.”

Claude Wickard and FDR.jpg

“Those justices decided the tiny amount of wheat on Filburn’s farm impacted the entire country and they knew they were increasing government’s power to a level never really considered before,” McEowen adds.

Wickard vs. Filburn became bureaucratic bedrock, and with SCOTUS’ ruling in hand, Congress and the U.S. government began regulating activity in a granular manner, down to the actions of individual citizens—all the way from Filburn’s farm to the Endangered Species Act to Obamacare implementation.

Astoundingly, Roscoe Filburn’s grain was the key that picked the lock on the present age of government regulation.

The Looming Bushels

Born in 1941, Filburn Jr. was 1-year-old when his father’s case went before SCOTUS.

“My dad knew he was going to lose,” Filburn Jr. says. “But win or lose, he didn’t like the government telling people how much wheat they could grow or what they could do with it. He didn’t believe it was right and he knew what it would lead to in other areas of life.”

WHEAT CUT LOAD.jpeg

In 1985, Filburn suffered a stroke and died two years later at age 85. “Honest. Hardworking. Trusted. He understood the government’s position about his wheat—and he didn’t agree in the least and fought with everything he had,” Filburn Jr. adds. “That was my dad.”

“It’s ironic,” Filburn Jr. adds, “because he was by no means a farmer living in the past. He was instrumental in the development of farmland into residential and business areas of Dayton and he was comfortable with change. But he wasn’t comfortable with losing freedom and he believed the Commerce Clause had been twisted from its original meaning.”

In 1829, 42 years after writing the Constitution, Madison penned a letter to Virginia state senator Joseph Cabell, emphasizing the true intent of the Commerce Clause as a: negative and preventive provision against injustice amongst the States themselves; rather than as a power to be used for the positive purposes of the General Government.

ROSCOE FILBURN OHIO FARMER.jpeg

Roughly 240 years after the Constitution’s framing, and 195 years after Madison’s letter to Cabell, and eight decades after SCOTUS’ monumental Wickard decision, Filburn’s bushels loom large.

“A little wheat on a little farm was used by the government to regulate all aspects of America,” McEowen concludes. “That is essentially limitless power.”

Roscoe’s Rebellion: Ohio Farmer’s Fight Against Federal Power Still Echoes When Roscoe Filburn fed his family and cattle without government approval, the Ohio farmer charged into one of the most consequential fights in U.S. history. Chris Bennett • September 12, 2024

https://www.agweb.com/news/policy/roscoes-rebellion-ohio-farmers-fight-against-federal-power-still-echoes

For more articles from Chris Bennett (cbennett@farmjournal.com or 662-592-1106)

☆

Comparing history to the events of today for an expectation of the future, for our world and mankind as a whole.

Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research.

☆